Presented at the conference “Virtual Adolescence” University College London, 9th February 2013

Ernest Jones suggested “that adolescence recapitulates infancy, and that the precise way in which a given person will pass through the necessary stages of development in adolescence is to a very great extent determined by the form of his infantile development" (Jones, 1922) In this re-editing of infantile development, the issues and solutions involved in what Lacan called the Mirror Stage are particularly important.

Before I get to the main body of the paper, I have to explain quickly a few basic Lacanian ideas around the self and other - subjectivity and what you might call object relations, which are quite different from ideas of the psychoanalytic mainstream but which also have points in common. First of all, taking his lead from Freud’s use of the word ‘Ich’, Lacan used the ‘I’ - ‘Je’ - in the place where many non-Lacanians would use ’ego’. His view of ‘ego’ is of an agency that while it forms the necessary mediating surface between the psyche and the external world, is also a largely fictional creation that must repress unwanted truths about itself. If you remember, Freud often pointed out that resistance in psychoanalysis issued from the ego. The fiction of the ego is created in a process exemplified by the Mirror stage - which I shall come to.

The concept of ‘otherness’ is also central and Lacan posits the Subject as coming into being by means of its relationship with otherness - which is not too dissimilar from Freudian or Kleinian views of the building of the psyche through object relations. But for Lacan, ‘otherness’ took two forms: le petit autre (small other) and le grand autre (Autre or Other with a capitalised first letter). Le petit autre is not a real ‘other’ but the reflection and projection of the ego and dependent upon image. Apart from the small other seen and recognised in the mirror as oneself, other people are ‘little others’ - suitable objects of projection and identification. The Other - with a capital ‘O’ - I shall call it the Great Other for simplicity - indicates a radical otherness which is beyond the Imaginary and comes from language and the laws that govern reality - le grand autre belongs to the Symbolic order. At the very beginning of life, the baby is exposed to the Great Other in the psyche of its mother; as the child grows, it forms its own Great Other, drawn from its exposure to that of many little others, including the wider family, teachers and very importantly for the adolescent, friends.

Now to the Mirror Stage. “[The Mirror Stage] sheds light on the formation of the I as we experience it in psychoanalysis” wrote Lacan. For the adolescent the question of the I in “who am I?” or “what do I want?” is absolutely central. In early childhood the mirror stage is an intellectual achievement, the logical and conscious discovery of the concept of ‘I’ thought for the first time as one, unique and different from others. This epiphany is triggered by the observation of an image that the child suddenly understands as representing himself. The process needs the ‘catalytic’ presence of the great Other (of the mother for the young child). It is the gaze of the Other, that triggers the thinking process:

-Who is this one in the mirror?

-It is me

-This is the way she sees me

However, as soon as this realisation occurs, there must be a negotiation between the newly found I and its image, which does not fit its expectation, does not feel like the ‘I’ feels about itself. The image imposes on the ‘I’ certain qualities that it does not necessarily want, and does not show qualities the ‘I’ feels it has. A split is introduced between the ‘I’ - the true Subject - and the object whose image is perceived, and the first answer to this is the constitution of an imaginary I, the ego. The ego is the result of a negotiation between perception and phantasy, between representation (internal object) and perception (external object), ideal ego and external reality. Freud uses the important concept of Bejahung (“the affirmation of what is”) to explain that the acceptance or affirmation of an image, requires an act, not simply that something has been perceived, but that it is accepted psychically.

Lacan said of the idea of whole self precipitated by the baby’s encounter with its specular image: This form would have to be called the Ideal-I… it will also be the root stock of secondary identifications… this form situates the agency known as the ego prior to its social determination in a fictional direction that will forever remain irreducible for any single individual, or rather, that will only asymptotically approach the subject’s becoming, no matter how successful the dialectical synthesis by which he must resolve, as I, his discordance with his own reality. In other words, the ego in Lacan’s view is first almost impossible to distinguish from the ideal ego constructed from the virtual image seen in the mirror around primary identification with the mother. It is therefore a fiction shaped by the imaginary scenarios that the young child produces before these come into contact with reality and in social interactions.

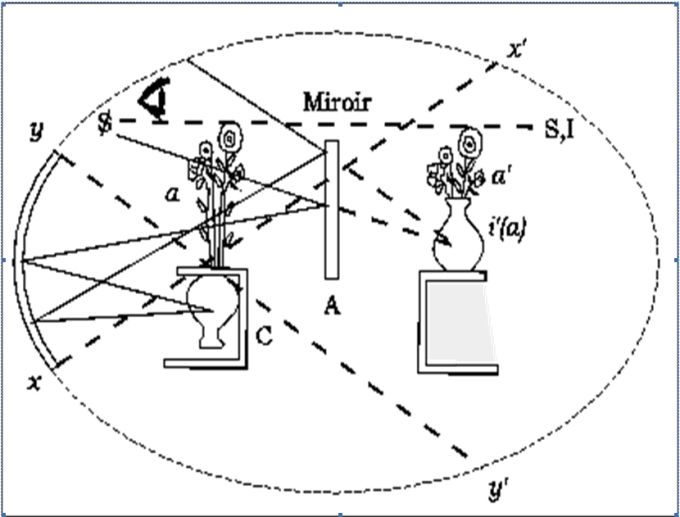

The Mirror stage - Lacan’s first public paper - later gave rise to an elaboration called the Optical Schema (1953-1954). This uses a fun optical illusion in which an observer sees flowers in what is in reality an empty vase.

A is a plane mirror

In yx is a concave mirror

I’(a) virtual image

$ the subject

S,I the subject’s image/ ego ideal

x’y’ real cone

C the box

In the box we find the real of the body to which the subject has little access. The curved mirror represents the nervous system which produces an image of the body. The subject has access to this image only through another image, the specular image reflected by the plane mirror representing the Other. In other words, at this point, it is the social rules and mores in the mind of the beholder that produces the image. Lacan calls it the ‘place of the Other’. In that space, at the point at which the image of the Subject would be found - SI - the ego ideal is constituted; this point is slightly outside the imaginary field of the plane mirror - both not quite visible in the mirror but of crucial importance as it is because the subject focuses on that point that the optical illusion becomes visible to it. In order to see the illusion, the subject ($) has to be between certain points (within the cone) and in the symbolic realm. If the subject is outside that cone he/she will perceive only chaos.

The teenager faced with the physical changes of puberty has to reconsider his/her image as a consequence of the changed gaze of others: parents, siblings, peer group etc. The new image he or she sees in the mirror is surprising, sometimes pleasing, but more often disappointing or worrying. Its constant changes and developments produce a succession of shocks and a cascade of libidinal implications. A new fiction must be written which becomes the teenager’s ego. Faced with the task of re-inventing him/herself, the adolescent works on his/her image and creates a narrative appropriate for a changed ideal-ego (the narcissistic ideal of omnipotence first constructed by the infant around a primary identification with the mother) and ego-ideal - the way the subject should be according to social rules and mores - the imaginary Subject always just out of sight in the optical schema.

Until quite recently the process we have been discussing involved a baby, other beings and the baby’s reflection (in a mirror, in the mother eyes, her discourse etc.) There was an inescapable set of parameters constituting the rules of the engagement. What has changed? Firstly the place where the confrontation between the ‘I’ of the young person with his/her image takes place has shifted from the external world towards a virtual world that is constituted in the Imaginary and its interface, the computer screen. The image is therefore not the constantly shifting one that the brain sees in a mirror as the result of real-time processing of sensory data, but one that has already been processed - chosen, frozen and even sometimes photoshopped - a pre-made external image that most closely fits with the ego-ideal. The image in the screen is true because others can see it, can forward it, can ‘tag’ it; its truth is validated by being seen by the multitude and its value is proportional to its popularity. The Other represented in the optical schema by the plane mirror is replaced by the multitude of small others, alter egos, objects of fascination and sources of hatred. The place of the mother for the baby becomes occupied by the siblings for the teenager. From the symbolic realm there is a shift to the imaginary: no more rules, weaker taboos and no need to refer to the signifiers of the mother tongue, any abbreviation/neologism will do. [R U :) ?]. Narcissistic competition knows few boundaries and perversion is a good way to attract attention: exhibitionism, sadism, masochism are the norm. This implies that what may be judged indecent by one’s parents or teachers is often deemed acceptable on one’s facebook page. Obviously, doing things that go against your parents’ value system is a defining factor in adolescence, but the difference here is that in the virtual world, a judgment that one’s actions may or may not be transgressive does not take place - the distinction between reality and make believe is erased. The virtual teenager does not do it ‘to shock’ and is surprised that it could. The problem is not in doing stuff your parents don’t approve of but the unrival-able seduction[1] (in the Winnicottian sense of a cathexis in which the subject has no choice) of the narcissistic gratification provided by the virtual social network. It robs all but the most mature or immature adolescents of conscious choice. The risk to the adolescent is that like Narcissus, fascinated by the perfect image in the water and overwhelmed by his enjoyment, he or she will stop acting and be unable to love anyone or anything else but this image, and will cut himself/herself from the world of the living. The image has become the determinant of experience. I have observed a young couple on a date in a restaurant spending most of their non eating time taking photographs of themselves and looking at them together; as if they could only experience the event when observed on a screen. It appeared more important to look like you were having a good time than having a good time. In the balance between object cathexis and ego cathexis, the gratifications provided by the screen-as-mirror are so enormous that they weight the libidinal cathexis of the adolescent far too heavily in the direction of the ego (narcissistic cathexis). How could anything outside the realm of narcissism - making beautiful music or paintings, learning about the natural world or ancient history etc possibly attract libidinal cathexis in the face of such competition from the ego as object ?

In this context what sort of ego ideal is constituted, at the point (SI) on which the subject focuses to make the optical illusion visible? The ego ideal is re-edited according to the new way in which the subject must behave in order to respond to the expectations of or set by, not the old symbolic authority but the new representatives of authority: the ‘popular set’, the worm eating ‘celebs’ of television programs, or the entirely virtual characters of video games. The Great Other is replaced by a world of phantasy and intersubjectivity unmediated by laws tried and tested and formulated over the history of civilisation. The subject derives its expectations from the behaviour and qualities of the new representatives of authority: expose yourself, be shallow, be omnipotent, destroy your rival etc. It is generally held in psychoanalytic theory that one of the main tasks of adolescence is precisely the re-editing of the ego-ideal to move away from that provided by the parents’ views. However, if the usual process involved finding alternative ideals - usually slightly older individuals - whom the adolescent could look up to as they once looked up to their parents, what is problematic in the virtual world is that the ideal images found there do not respect the reality principle and encourage ego cathexis rather than object cathexis. Without object cathexis there is no creativity; when the ego is the only object cathected, the only thing created is more and more images of oneself. And playing the air guitar does not even makes you fit for a punk group.

The ideal ego, constructed around a primary identification with the mother, is re-edited in adolescence through new identifications with adult figures but also to peers. The virtual world offers as we have seen new and virtual models of identification, which set goals not necessarily bound by the reality principle. In their quest for perfection, teenagers are also able to do something that their predecessors could only do in a limited way and by immense effort: they can change their reality to enjoy the imaginary consequences of the change. No need now to learn to play an instrument, go to the gym or study, from photoshop to the virtual creation of an avatar, I can be represented by a creature whose qualities do not match mine. In the optical schema, the subject can now choose the flowers and change them if necessary. Reality - so disappointing compared with your virtual self - then becomes the problem, and the solution is to spend more time on electronic media, your eye in the cone in which the image of your narcissistic truth is displayed. The virtual solution can be seen as a perverse solution to anxiety: as long as the virtual image is intact I do not feel any. Reality can be denied in the same way that the fetishist can deny castration. The success of the individual is tied to the rate of approval of the virtual image: the number of ‘friends’ who click on the ‘like’ button, who re-tweet your wit and wisdom etc. If the anorexic patient measures her self-worth in pounds, the virtual teenager derives his/her value from the amount of exposure/agreement harvested. Personal value is no longer linked with any real value, ‘real’ being measured by the Great Other (eg getting approval because you have done something exceptional); it is determined purely intersubjectively and usually by force of aggression. It is a Lord of the Flies scenario.

One of the dangers of such a process is that one’s value can, like shares at the stock exchange, go up or down. Nothing can be done to stop a crash as the power is with the multitude of small others who do not have your best interests in mind. The virtual world allows the easy and relatively safe expression of dislike, of unbridled aggression and the encouragement of others’ aggression. The young person who derived intense gratification from the recognition of his/her image will be hurt in equal proportion by its demise, and what appears as a silly incident to a therapist who grew up in a pre-electronic world can be a narcissistic wound on par with a mutilation for a teenager of this era. An added degree of complexity lies in the fact that the virtual world is accessible at all hours and almost everywhere. The home, the bedroom even one’s bed becomes linked with the rest of the world like never before. The distinction between private and public is blurred and the individual exposed to bullying finds that there is no place or time where they are safe. The violence of the attacks is linked with the particularity of a specular relation in which the mirror is composed of elements similar to the subject. When the plane mirror of the optical scheme represents the Great Other, the asymmetry with the Subject limits rivalry; when the mirror is the small other, it allows the possibility that one’s success is the other’s failure. Then only the fear of retaliation restrains the desire to undermine others.

Taking further the analogy of the optical schema, we see that with the virtual image the individual has the possibility of manipulating the imaginary qualities of the object (the flowers). However, the vase in its box remains beyond reach. The real of the body cannot be manipulated and this can be experienced as persecutory, as something that gets in the way of perfect enjoyment. That primary division in the subject between its experienced self and its object image is widened. When the adolescent inhabits the virtual world, his or her body is often neglected (hygiene, eating etc.) or even hurt, as when a young person engages in a dangerous activity in real life which in the virtual world they are able to master - from Parkour to cases such as the Taiwanese teenager who collapsed and died at an internet cafe after playing Diablo 3, a popular online video game, for 40 consecutive hours. The body can be also treated with contempt in sexual activities enacted for their imaginary content, as if what was done did not involve one’s real body but only its image. Sex is as virtual as killing in a video game; what is important is to do what I imagine I am expected to do, or from the point of view of the ego-ideal, to behave in the way required to impress the group.

The electronic age has arrived and is here to stay. There is no point demonising it and repeating the fearful comments of our forebears regarding the telephone or the television. However, what we should keep in mind as professionals, are the potential effects of virtual reality on crucial phases of an individual’s development as it undermines the reality principle, encourages ego cathexis rather than object cathexis and distorts the process of identification by which in adolescence, one re-edits one’s image.

Bailly, L. (2009) Lacan, A beginner’s guide. One World, Oxford.

Lacan, Jacques. (1988). The Seminar of Jacques Lacan, Book I, Freud's Papers on Technique (1953-1954). (John Forrester, Trans.). New York: Norton.

Jones, E. (1922) Some Problems of Adolescence, Papers on Psycho-Analysis, London: Baillière, Tindall & Cox, fifth edition, 1948.

[1] Thanks to Sham Bailly for pointing this out to me